Ready to launch your own podcast? Book a strategy call.

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Conversation

Highlights

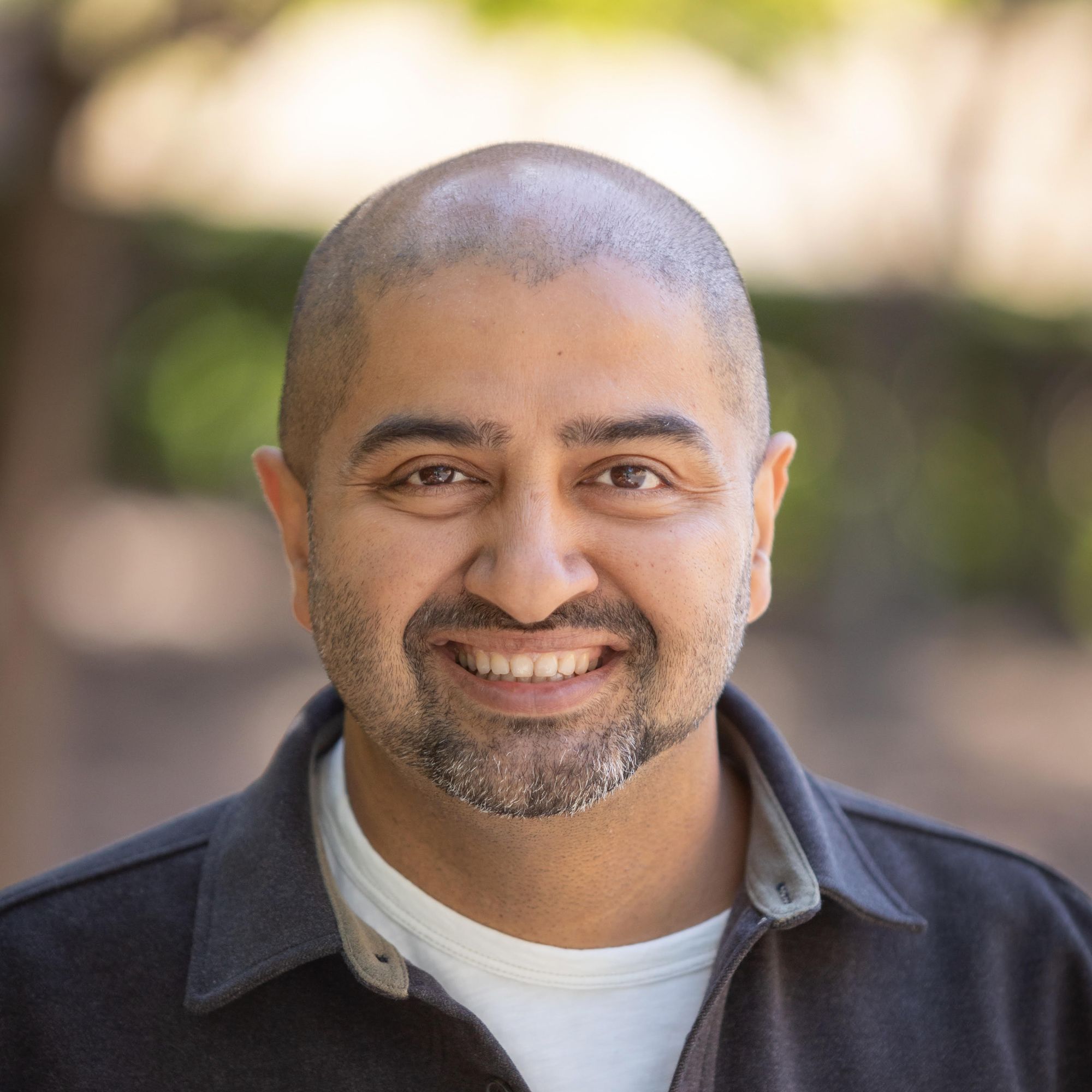

How Density Built a $1B Business by Measuring the Invisible: Andrew Farah’s GTM Journey

It began with a coffee shop line on a snowy day.

In 2014, Andrew Farah and his friends were tired of trekking through feet of lake effect snow in upstate New York to reach their favorite coffee shop, only to find a 20-minute line waiting for them. The frustration sparked a simple question: “Why can’t we remotely know how many people are in line at that coffee shop?”

This seemingly straightforward problem led to the creation of Density, now a $1B company measuring how space is used across the world. In a recent episode of Unicorn Builders, Farah shared the winding go-to-market journey that transformed a weekend project into a unicorn company.

The Deceptively Hard Problem of Counting People

When Farah and his team first explored the market, they found hundreds of products claiming to solve the people-counting problem. But reality quickly set in.

“We looked around for some stuff and we found hundreds of products that said that they could do this and they all sucked,” Andrew recalls. “And so we’re like, this can’t be that hard to build. And 11 years later, I can tell you it’s really hard to build.”

The challenge was far more complex than anticipated. Thermal sensors failed when people entered from rain or snow. Phone tracking systems counted multiple devices as separate people. Passive infrared created false positives.

What initially seemed like a straightforward engineering problem turned into an 11-year quest to build technology that could truly measure how space is used. According to Farah, five critical requirements had to be met:

“There are five things that matter when you’re in this space. You gotta be real time, accurate, anonymous, low cost and self installable,” Andrew explains. “And I joked on X recently that each one of those five has cost me two years of my life.”

The Unlikely Market Discovery

Density’s first attempts at commercialization involved skating around San Francisco, trying to convince coffee shops and bubble tea stores to install their early prototypes. But the real breakthrough came from an unexpected source.

A LinkedIn employee named James Woodwell saw Density’s early counting technology and invited Farah to tour their campus. “He’s like, you see all those buildings? I have no idea how they’re used, and I can’t put a camera in any of them,” Andrew remembers.

This conversation opened Farah’s eyes to the enormous corporate real estate market – a sector spending billions on space with almost no data on how it was actually being used.

“If I have a thousand seats, I will assign a thousand heads to those workstations,” Andrew explains about traditional corporate thinking. “Well, it turns out when you do that, about 60% of them show up. When only 60% of people show up to a building that was designed for a thousand people, it means you can fit an extra 400 into that building without any additional costs.”

This insight revealed a massive inefficiency hiding in plain sight: approximately 40% of commercial real estate (worth $150 billion) sits vacant but paid for. And as Farah points out, “When you look at a company’s costs, real estate is typically the second most expensive thing next to payroll.”

The Pandemic Paradox: Crisis as Catalyst

When COVID-19 hit in 2020, Farah wrote a worried memo to his team: “What happens to a people counting company when everybody goes home?”

But counterintuitively, the pandemic accelerated Density’s growth rather than hampering it. As workplaces emptied, CFOs began asking fundamental questions about their real estate investments.

“When everybody went home, CFOs turned to their heads of real estate and said, ‘Hey, how many buildings are we going to need when they all come back?'” Andrew recounts. “And the heads of real estate were like, ‘We’re not really sure.’ And the CFOs are like, ‘No problem… Out of curiosity, how much were we using before the pandemic?'”

The uncomfortable silence that followed revealed a startling truth: most companies had no data on their pre-pandemic space utilization. This realization triggered Density’s largest growth quarter during the crisis.

Templeton Compression: Designing for the First Meeting Close

Density’s evolving go-to-market strategy centered on what Farah calls “Templeton Compression” – the ability to close a deal in the first meeting with a prospect.

“When you close the deal in the first meeting… we call the sales cycle the process of getting through the paperwork,” Andrew explains. “The sales motion should happen in the first 30 minutes. And the only way you can do that is with a sales ready product.”

This philosophy guided Density’s product development. Rather than focusing solely on building features, they designed their offering to accelerate the sales cycle as quickly as possible. Farah believes that “your sales motion is an outflow of the product you build, more so than the team you construct.”

The introduction of their latest product, “Waffle,” exemplifies this approach – a small, self-installable sensor that finally achieves all five critical requirements Farah identified. The sales conversations with this product are completely different from their earlier offerings, even though they solve the same fundamental problem.

Side Quests and Viral Moments

Density’s growth strategy also leveraged what Farah calls “side quests” – projects tangential to their core business that showcase their unique perspective.

One particularly successful example was their visualization of federal building utilization data. After Elon Musk retweeted Farah’s analysis, the project generated 9.7 million impressions in 24 hours, revealing that the busiest moment in a quarter of the federal portfolio saw only 9% utilization.

“Peak utilization in a quarter of the Federal portfolio was 9%. Busiest moment was 9% utilized. Their best in class was 24% utilized,” Andrew shares. “So it’s what we said in the report. It’s a monument to absence.”

This side quest not only generated massive awareness but reinforced Density’s core value proposition: measuring space utilization reveals enormous inefficiencies that most organizations don’t even realize exist.

The Hardware Advantage in an AI World

While many startups focus exclusively on software, Density embraced the challenges of hardware development. This decision, while difficult, created a distinctive competitive advantage.

“It’s a lot harder to LLM your way into hardware,” Andrew notes. “We don’t get ‘oh, like you went from zero to $20 million in three months. Congratulations. Let’s do a $4 billion round’ which is actually happening right now, which is totally nuts.”

The hardware-focused approach required extraordinary persistence. As Farah puts it: “Not dying is kind of a skill you’re supposed to get good at as a founder, because those that don’t die, they eventually succeed because you can only not die for so long without succeeding.”

The Future: Measuring the Built World

Today, Density’s technology is deployed in Delta’s airport lounges, corporate offices worldwide, universities, libraries, and government buildings. But Farah’s vision extends far beyond:

“There’s about 3 to 4 trillion square feet of space in the world and we don’t know how any of it is used,” Andrew explains. “And if you can figure out how the world is used, you sort of earn the right to redesign it.”

This ambitious vision – to measure the built world in order to redesign it – represents the long-term opportunity Farah has been pursuing for over a decade. By solving the deceptively difficult problem of accurately counting people in spaces, Density has positioned itself at the center of how buildings, cities, and physical spaces will evolve in the coming decades.

For B2B founders, Density’s journey offers powerful lessons in persistence, finding hidden market opportunities, and designing products that compress sales cycles. Most importantly, it demonstrates that solving fundamental measurement problems – even through the challenging route of hardware development – can create enormous value when applied to the right markets.

Actionable

Takeaways

Compress your sales cycle by building a "sales-ready" product:

Andrew referenced Jim Goetz's "Templeton Compression" philosophy, which advocates for products that can close deals in the first meeting. The ideal B2B product should allow prospects to immediately see themselves using it, turning everything after that initial demo into "just paperwork." B2B founders should design products that create those "aha moments" for prospects as quickly as possible.

Design your product to accelerate the sales cycle:

Andrew emphasized that "your sales motion is an outflow of the product you build, more so than the team you construct." When Density finally achieved all five critical attributes (real-time, accurate, anonymous, low-cost, and self-installable), it dramatically changed their sales cycle and motion. B2B founders should prioritize features that remove friction from the buying process over those that merely add capability.

Demonstrate real-world problems to prospects with data they can't ignore:

Density's most powerful sales moments came from showing customers data they couldn't access elsewhere - like when Linkedin's workplace strategist realized he had no visibility into how their buildings were used despite managing millions in real estate. Effective GTM strategies often involve revealing to prospects what they don't know about their own operations.

Turn side quests into viral marketing opportunities:

Density's public visualization of federal building utilization generated 9.7 million impressions in 24 hours after being amplified by Elon Musk. The project began as a "side quest" analyzing public data about government building usage. B2B founders should look for opportunities to repurpose their core expertise into shareable, data-driven content that demonstrates their unique insights.

Find problems hiding massive inefficiencies:

Density discovered that 40% of commercial real estate (worth $150 billion) sits vacant but paid for—a problem that existed before the pandemic but wasn't visible to decision-makers. B2B founders should look for high-value problems where crucial data is missing, as solving these visibility gaps can unlock enormous customer value.