Ready to build your own Founder-Led Growth engine? Book a Strategy Call

Frontlines.io | Where B2B Founders Talk GTM.

Strategic Communications Advisory For Visionary Founders

Actionable

Takeaways

Patience in Deep Tech:

The semiconductor startup timeline requires thinking in 3-5 year horizons for go-to-market, not the typical 1-year timeline of software startups. SEMRON spent four years developing their core technology before reaching process freeze and beginning customer demonstrations.

Focus on Enterprise-Scale Relationships:

Rather than pursuing a broad customer base, SEMRON targets 5-6 major customers who can each generate millions in revenue. This shapes their entire go-to-market approach, emphasizing deep technical engagement over traditional marketing.

Leveraging Technical Feedback Loops:

SEMRON's strategy involves working directly with customer engineering teams to deploy proprietary AI models on their hardware. This creates valuable feedback loops that reshape product development based on real application needs.

Strategic Location Advantages:

While Dresden may not be Silicon Valley, its history as Europe's microelectronics hub provides crucial advantages for semiconductor startups - from talent to manufacturing partnerships with companies like TSMC, Infineon, and Global Foundries.

Cost-Driven Innovation:

True hardware revolutions happen when the driving technology becomes extremely cheap. SEMRON focuses not just on technical performance but on dramatically reducing the cost per compute to enable mass adoption of edge AI capabilities.

Conversation

Highlights

The Three to Five Year Reality: Why SEMRON’s Go-to-Market Strategy Breaks Every Silicon Valley Playbook

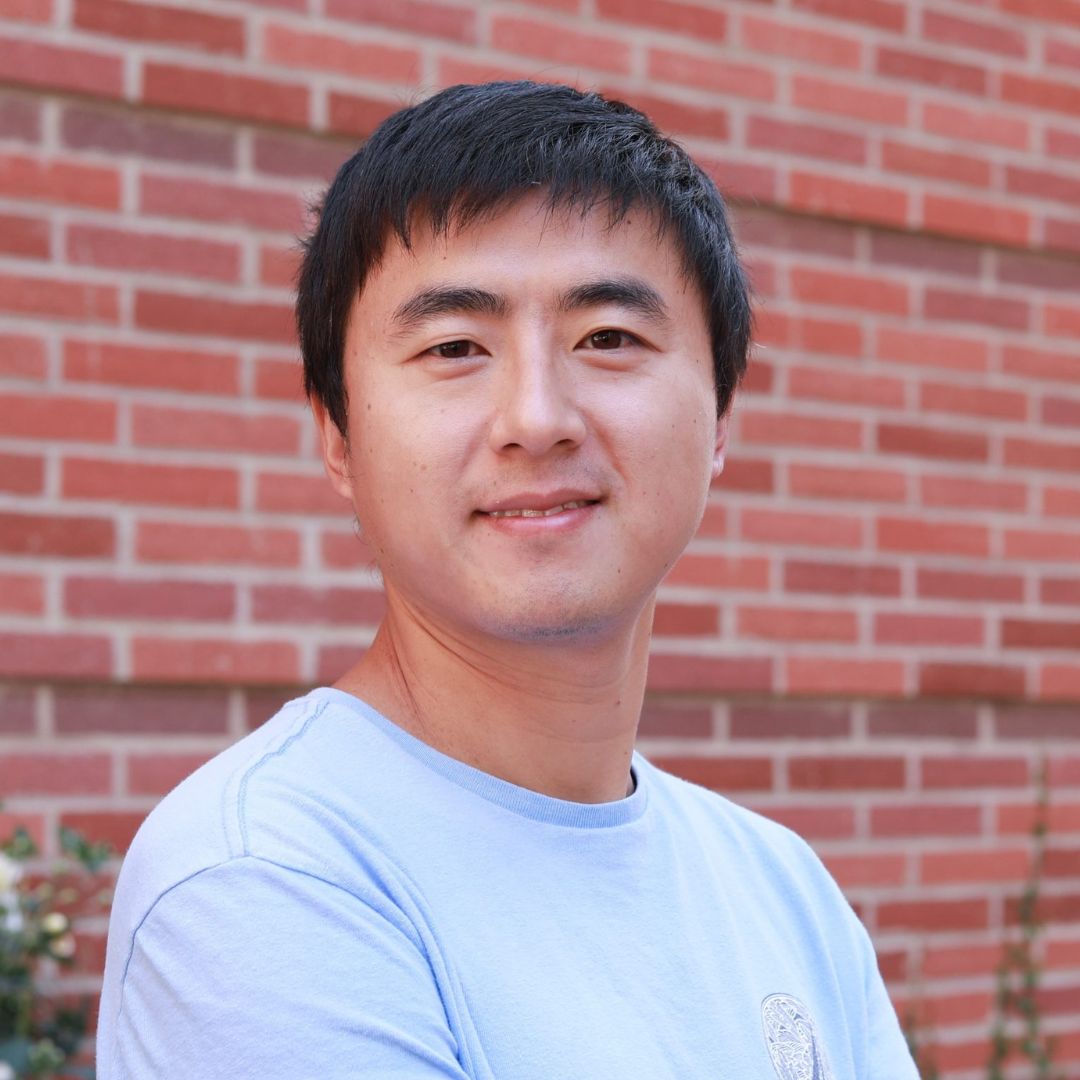

Most Silicon Valley founders obsess over growth hacks and viral loops. But what happens when your product takes four years just to reach the demonstration phase? In a recent episode of Category Visionaries, Aron Kirschen, CEO of SEMRON, an AI chip maker that’s raised $7.3 million, shared a go-to-market reality that most software founders never confront: building hardware means thinking in geological time.

The Timeline That Changes Everything

When Aron talks about go-to-market strategy, he doesn’t measure it in quarters. “As a semiconductor startup, you don’t have the timeline or the roadmap usually of 1 year for go to market to really have to think in three, four, even five years,” he explains. This isn’t a failure of planning. It’s the physics of the business.

The timeline depends entirely on where you start. If you’re working with existing semiconductor technology and just designing a new chip, you’re looking at one to two years. Start with a new semiconductor device like SEMRON did, and you’re talking three to five years because “you really have to open the semiconductor process and make some changes there together with the foundry.” Go even further with new materials beyond standard silicon, and you’re committing to eight to ten years.

For SEMRON, four years in means they’re just now “close to process freeze.” That’s when development and testing wrap up, and the real go-to-market work finally begins.

The Customer Strategy That Defies SaaS Logic

Here’s where SEMRON’s approach diverges completely from typical B2B playbooks. Aron is explicit about their customer strategy: “We do not or will not likely won’t have millions of customers. For us, it’s more like having five, six big entities that is generating millions of revenue.”

Five customers. Not five thousand. Not fifty thousand. Five.

This fundamentally reshapes what go-to-market means. “It’s very intense, very technical, very detailed, of course, but it is less standard marketing,” Aron notes. There’s no funnel optimization, no conversion rate testing, no demand gen campaigns measured in thousands of impressions.

Instead, it comes down to something deceptively simple: “You have to sit down with their engineering team, with our engineers, and figure it out how we can make it work.”

This isn’t marketing as performance art. It’s engineering as sales.

Why Demonstrators Are the Entire GTM Motion

For hardware companies like SEMRON, the demonstrator isn’t just a sales tool. It’s the entire go-to-market strategy compressed into one deliverable. “For us, it all comes down to these demonstrators going out to customers, showing them our FPGA together with our hardware,” Aron explains.

But building demonstrators in 2025 means doing something that would have been foreign to semiconductor companies a generation ago: massive software work. “Even though we are hardware company, so today hardware means you have to do a lot of software,” Aron points out.

The process SEMRON follows reveals what sophisticated customer engagement actually looks like. They receive proprietary AI models and benchmarks from potential customers. Then they deploy these models on their hardware, which they currently have to emulate alongside test structures. “We try to make it fit into that,” Aron says. “And so we discussing with them about, okay, what can we do about your models? And come back with a nice performance simulation.”

This iterative, technical dialogue is where deals get made or lost. Not in pitch decks. Not in conference booth demos. In detailed engineering discussions about how specific models perform on specific hardware.

The Customer Feedback Loop That Takes Years to Access

Perhaps the most striking insight from Aron’s experience is what it feels like to finally reach customers after years of development. “For a semiconductor startup that for three, four years worked like it feels, it felt like swimming in the ocean. And you never had the real feedback,” he reflects.

The market feedback during those early years was superficial at best. Conversations where potential customers said “we might be interested, blah, blah,” and investor due diligence where VCs reached out to gauge whether the technology held potential. But none of that provided the granular understanding needed to actually build the right product.

Now, as SEMRON enters substantive customer discussions, everything changes. “It’s really like we understand what they need in an application. And of course it completely reshapes your coordinate system. You never thought about that before,” Aron admits.

These aren’t casual conversations. SEMRON is engaging with “very big, well known companies that are market leaders in their application or in that vertical.” The specificity of their requirements, the depth of their technical challenges—this is the feedback that actually matters, and it only arrives after years of development work.

The Cost Economics That Enable Revolution

Underlying SEMRON’s entire go-to-market thesis is a simple economic truth: cost matters more than efficiency. Aron is blunt about this: “I know that’s an important thing, but you also have to talk about cost, right? Cost per compute.”

He illustrates the problem clearly: even if you could make an energy-efficient AI solution using an Nvidia graphics card in a smartphone, “we would not be able to make a product out of it because nobody would pay for like $5,000 more for something like that or even $200 more.”

The magic number? “We really have to be like let’s say 20, $30.”

This cost constraint shapes everything about SEMRON’s product strategy and, by extension, their go-to-market approach. They’re not selling marginal improvements. They’re selling the economic viability of an entirely new category of devices. As Aron puts it, “We find a way or manage to build a chip. It costs a couple of dollars. Able to run large language models with billions of parameters as continuously power consumption of less than 500 milliwatt.”

That’s the promise that opens doors with those five or six major customers.

What 2025 Looks Like

As SEMRON moves into 2025, Aron’s focus is clear: “It’s about customer engagement.” Not customer acquisition in the traditional sense, but deep, technical engagement. For the first time, they’re sitting down with engineers from major companies, receiving proprietary models, and proving out performance.

“I’m really looking forward to next year,” Aron says. “I can’t wait to start. I mean, I’m looking forward to Christmas as well, but I’m really excited that 2025 will start.”

For hardware founders, SEMRON’s journey offers a crucial lesson: your go-to-market timeline isn’t a failure. It’s a feature of building something that requires fundamental innovation. The key is aligning your entire strategy—from funding expectations to customer targeting to team building—around that reality, not fighting against it.

Sometimes the best growth hack is patience measured in years, not weeks.